A walk to Stonehenge through one of the richest archaeological landscapes in the UK.

Part II – From Henge to Henge, Marden to Durrington Walls, Wiltshire

This is part two of a personal pilgrimage from my house in Calne, Wiltshire to Stonehenge for the winter solstice. I am walking the 28 mile route across central Wiltshire with my friend Clive, a born-and-bred Wiltshire man who frequents the same pub as I do in Calne. If you haven’t already, I suggest you read part I of our journey first which you can find here: Stonehenge Pilgrimage Part I

You are joining us now as we arrive for lunch in Marden, a lovely village in the Vale of Pewsey, having spent the morning walking south east across the Marlborough downs and half way across the vale. Our partners and my 7 year old son have arrived at the pub ahead of us and give us a cheery welcome as we walk in the door, a log fire is burning in the hearth. My wife, Siân, has brought me some dry leggings and walking trousers which I gratefully accept and change into, my others having been soaked by a morning storm. The pub is very quiet with only two other tables occupied.

Chatting to our waitress we discover that, for the second time, we are lucky to have chosen today, 19th December, for our walk. Had we walked on the 18th our route this morning would have taken us through a hunting party above Calstone and, had we chosen the 20th, this pub, The Millstream, would have been shut. Our waitress explains that the managers don’t want the pub to be swamped over the Christmas holidays when the UK government are lifting travel restrictions for four days. By closing the pub they are removing one option as a place for village families and returning relatives to gather and possibly spread the virus. We are all extremely relieved that they are open for us as we peruse the specials of the day. One look at the menu and I have no hesitation knowing what to order. To explain why I need to share some information about the UK’s enigmatic henge monuments, so please bear with me…

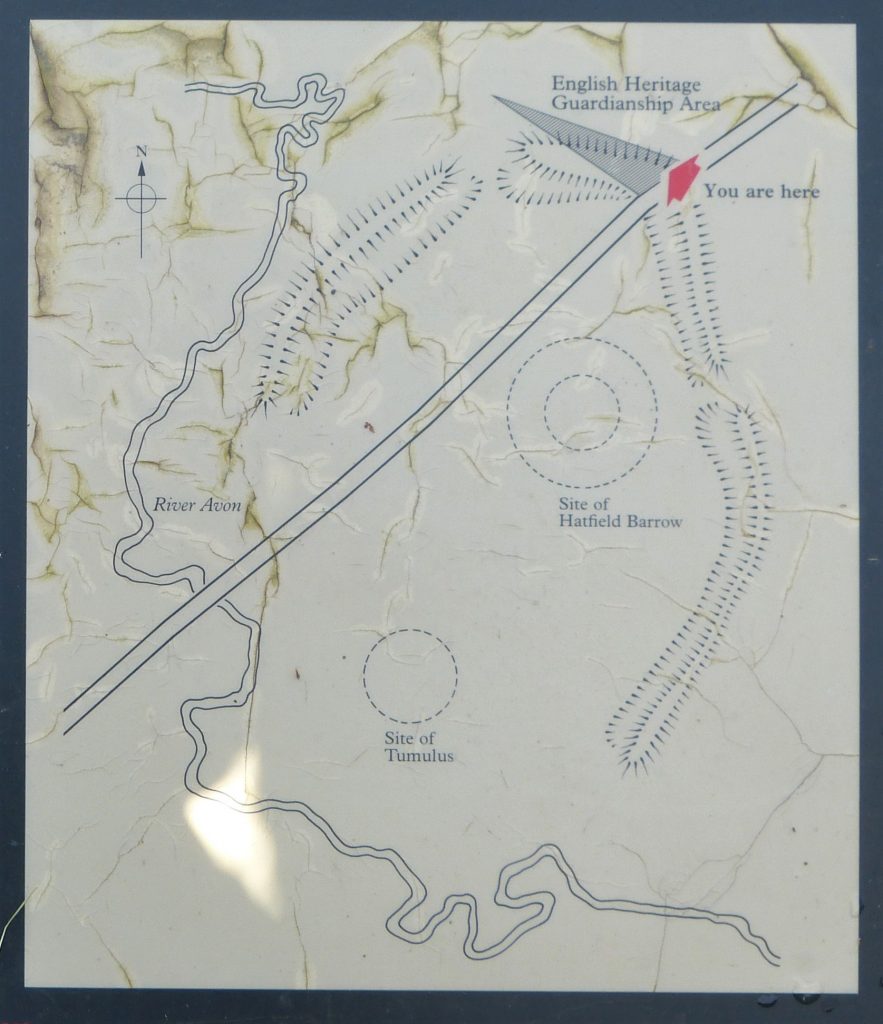

Just before lunch Clive and I walked through Marden Henge a Neolithic monument that lies just to the north of the village. At that point we were keen to get to the pub but I’d like to take you back there now on a virtual tour as we quench our thirst with Wadworth’s beers. The vast majority of people have never heard of Marden Henge, even those who live within walking distance, and yet four and a half thousand years ago this enormous site must have been a very important place. To be fair there isn’t a huge amount to see here now but there is still enough to grasp at least the scale of this once great monument.

Henge monuments such as this date from the late Neolithic period, typically around 2,500 BC in England although there are examples dating from five hundred years earlier, such as at Thornborough in Yorkshire and on Scotland’s Orkney Islands. Throughout the Neolithic period we shared many cultural similarities with continental Europe but, surprisingly, henge monuments appear to be unique to the British Isles. Found nowhere else, we have well over a hundred of them here.

This class of monument, which takes its name from the ‘henge’ part of Stonehenge, is defined by a couple of shared characteristics: they all have roughly circular ditches with a bank of the excavated material running round the outside, and they all have at least one entrance/exit through the bank and across the ditch. The commonly held opinion is that these circular banks and ditches enclosed a special, or sacred, space.

In part one I explained that the 25 mile long defensive structure called Wansdyke had its ditch dug to the north, in front of or outside the bank, forcing anyone attacking from that direction to cross it before attempting to clamber over the bank to the side of the defenders. With henge monuments, in nearly every case (one very notable exception being Stonehenge), the ditch is placed on the inside of the bank so is clearly not for a defensive purpose. It is perhaps, therefore, to keep something within rather than out of the enclosed area. What it was they were keeping in we shall never know of course but there are some interesting ideas out there.

Apart from the more prosaic suggestions (equally valid of course) that the arrangement might be to pen cattle or other domesticated animals, most ideas concern ritual use within the henge. Were the earthworks protecting the rites of a sacred ceremonial occasion? Was the henge a space that was reserved for a communion with a god? Or somewhere that a privileged few met with the souls of the ancestors? Or was it set aside for those ancestors’ spirits to hold meetings of their own? Whatever its purpose the monumental arrangement suggests that in those bygone times whatever happened in the henge stayed in the henge!

Where archaeologists generally agree is that despite sharing many characteristics not all henge monuments served the same purpose. And size is everything when it comes to those suggested differences. The enclosed area of a henge can be just a few metres in diameter, perhaps where the monument was for the private use of a few individuals or a family, or it can be enormous like this one at Marden, whose internal dimensions are 530m from north to south and 360m from east to west. The bank encloses an area of 35 acres (14ha) which Aubrey Burl in his book ‘Prehistoric Henges’ points out is ‘as capacious as a car park for sixteen thousand vehicles.’ (p. 42). Another huge example, with an average diameter of about 480m, is known as Durrington Walls which lies just two miles north east of Stonehenge. The henge here was built around a village that archaeologists believe housed the builders of Stonehenge as well as the many travellers that came from across the UK for the rituals and ceremonies celebrated there. And this is also our objective today.

During excavations, the henge at Durrington Walls divulged a lot of information about its occupiers. There was evidence of long forgotten structures, including incredibly rare houses buried beneath the grass and soil but, perhaps more importantly, they discovered rubbish dumps, or middens, as well as ritually deposited artefacts. To archaeologists middens are like treasure chests and those here at Durrington contained not gems, bullion and pieces-of-eight but vast quantities of pottery and datable animal bones.

Henge building coincides with a time when the UK inhabitants were using a type of pottery archaeologists call Grooved Ware pottery. In fact the era is defined by this pottery as that of the Grooved Ware Culture. The earliest examples of this pottery have been found in Orkney and date to about 3,000BC but by the time Marden henge and Durrington Walls were built the pottery and the culture associated with it had spread across the whole UK.

In the late 1960s excavations in the ditches of both Marden henge and Durrington Walls revealed Grooved Ware in huge quantities as they have at other late Neolithic ceremonial centres across the UK. Along with all the pottery discovered at Durrington Walls was a huge amount of animal bone, particularly that of young pigs about 9 months old, the remains of massive feasts. The age of the pigs which would have been born in spring suggests that these feasts were, crucially, held in midwinter. It is a long explanation but that is why, on our midwinter journey, it seems appropriate to choose the pork medallions in cream and mustard sauce for my lunch. On the table behind I hear Clive ordering the same without knowledge of the connection and I congratulate him on his very apt choice.

Sometimes henge monuments across the UK, such as at Stonehenge and Avebury just a few miles to the north of here, contain stones. But having a stone circle inside a henge is not the norm, the majority being just circular earthworks. There were no circles of standing stones here at Marden but the general idea of an enclosed space is still evidently the objective. There are two entrances through the bank, one to the north, through which Clive and I entered the monument and the other to the south east. There was also once a huge man-made mound in the centre. Called the Hatfield Barrow the mound was about a third the size of Avebury’s Silbury Hill and was still standing at 30 foot (9m) in the mid eighteenth century. Unfortunately by 1818 it had been completely flattened by the landowner and no visible evidence of it now survives.

Since 2010 English Heritage and Reading University have focused a lot of attention on Marden henge and other monuments in this area of the Vale of Pewsey. From 2015 I was fortunate to be involved in three years worth of excavations in and around Marden with Reading University Archaeology Department under the direction of Jim Leary and Amanda Clarke, so it is a particularly special place for me.

Sitting at our two tables, socially distanced as required, we pass a perfect hour and a bit, chatting, eating and drinking until a glance at my watch tells me we must get on our way. We have spent considerably longer here than I had planned, in truth, but it has been a really lovely lunch. With a skip and a hop we are back on our way, heading up the lane towards the plain, our families waving us, encouragingly, off. I know that we now won’t make it to Durrington before dark but most of the rest of the route there is a long a designated path, The Great Stones Way, so it should be easy enough to navigate.

We pass attractive houses, some of brick and thatch with mint green window frames and soon turn left up a narrow path that runs next to a thatched chalk wall, a curiosity of this part of Wiltshire. Shortly our way opens out into fields and before long we take a right angled turn to the south to walk along a straight field boundary. After crossing the Rushall to Devizes road we pass a round white sign that states No MoD vehicles and soon start to ascend a muddy track up towards the plain.

As we climb the escarpment out of the Pewsey Vale we pass another earthwork marked on the OS map as Broadbury Banks. It is, like so many other earthworks in the area, undated through excavation but probably dates to the Iron Age and may be part of an unfinished hillfort – it certainly occupies a commanding position overlooking the vale. We regularly turn to admire the view back to the north, the last time we will be able to see our morning’s route.

Passing a couple of walkers on their way down we soon find ourselves on Salisbury plain, the high chalk plateau which occupies about 300 square miles of southern Wiltshire. About half of the plain is owned by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) who started buying land here in 1898 during the Boer War. It is now the largest military training area in the UK and when walking here you often find your peaceful stroll is accompanied not just by the song of skylarks but by the less tuneful thumps of artillery and heavy machine gun fire.

Along with the MoD the plain plays host to an astounding variety of prehistoric sites, including most famously Stonehenge, and, strange as it may seem, the army’s presence has actually protected a lot of them. From the early twentieth century military hardware was rapidly developed due, mainly, to two world wars. With land at a premium farm machinery also improved; the plough, now pulled by mechanised tractors not horses, was developed to cut deeper into the earth. Unfortunately where the soil is thin the archaeology lies close to the surface and these developments made it instantly more vulnerable.

Furthermore, during this time, the development of nitrogen fertilisers enabled poorer soils, such as those on the chalk downlands, to be exploited. This combination meant that much of north Wiltshire’s high ground, previously only suitable for grazing sheep, was converted to arable land, the plough destroying a huge number of archaeological sites in the process.

However, throughout this period the archaeology of the MoD’s land fared much better. Most of the training area was left undisturbed by the plough and the main activity of the army’s big guns was kept to a few specific target areas. As a result many important prehistoric monuments remain upstanding, sites that would otherwise probably have been destroyed. In this unusual instance the sword has proved gentler than the ploughshare.

As we emerge onto the plain the guns are thankfully silent, all is quiet on this the northern front. We turn left onto the ‘perimeter way’ which encircles much of the plain’s army land. I have designed our route to cut the corner where the wide Pewsey Vale joins the Avon’s narrow valley, bypassing the villages of Rushall and Upavon. The grey-gravelled army track leads us first east and then in a sweeping arc to the south, keeping us for now on the higher ground. After a fairly featureless half hour under changing skies we arrive at the banks of Casterley Camp, an iron age enclosure.

This hillfort which stretches away to our left is remarkably symmetrical comprising a very large square enclosure. The 60 acre interior is surrounded by a single bank that is uniformly high and wide but not in anyway as impressive as the often enormous multiple banks of other Wiltshire hillforts. Indeed it is hard to see how the earthworks here could have performed much of a defensive role against the might of an invading Roman army. Its regularity makes it rather uninspiring compared to the rugged contour hugging lines of Oldbury and Rybury and others north of here, such as Barbury and Liddington, but it is nonetheless an important site. Excavation has shown that it was occupied during the Iron Age and then throughout the Roman period.

Two important events are occurring as we pass by this ancient earthwork: the day is noticeably drawing to a close and Clive is similarly slowing down. I am keen to get off the plain before darkness envelops us but my partner has developed a stiffening of the body that has significantly slowed his progress. I have only known Clive for eight or so years and have never been on an expedition with him but one thing I can guarantee is that he is not a quitter. The next hour or so will prove that.

We follow a pointing finger post to strike off across the open grass to reach a barn and turn left on a grass path parallel to a deeply rutted farm track. Some 4x4s are meeting at the high, open buildings of West Chisenbury Farm ahead of us, their headlights all lit in anticipation of an evening ramble. We turn right down a lane and then, as it bends to our left, carry straight on towards the hamlet of Compton. As we drop down between high hedges, stone tiled buildings come into view their lit windows bright in the gathering gloom. At the bottom a driveway leads off to the left, its entrance rather unusually guarded by two black antique field guns, presumably there just for decoration, which point away from us towards the main road. We have sneaked in behind them on our route off the plain and now need to work out where the path leads, dark as it is in this downland dip.

A sturdy gate bars the way to our right which leads into a very private looking farm yard and it is only after a few minutes of squinting at the map that we realise that this is indeed the way we need to go. The clanking of the gate and the rusty rasp of its hinges make me feel a little nervous but we have only gone a few steps when we see a kissing gate and a way marker. We find our way across a little bridge, past willow trees drinking deep of the stream, to the far side of a small field. It is really getting dark now, too dark for us to be aware of the huge burial mound that sits above us on the ridge.

A grassy track takes us out of the little side valley and gradually up again, traversing the slope of the Avon valley’s western bank. Vibrant, almost lurid green, mosses line our way in the glow of a thatched house below us, the ground pleasant and spongy underfoot. I have often looked up to this valley side from the road below and wondered if a path traverses the slope so it is good to be up here walking and, as we pass through a kissing gate, I even see a reassuring sign for the Great Stones Way.

At the top of the slope we pass some farm buildings and then drop down to join a very rough farm track past an electricity substation. The deeply rutted track, as we climb again, would be tough enough even for the freshest legs, and really doesn’t help Clive’s progress. It is now that I start to worry about Clive. He isn’t complaining but is clearly in a lot of trouble and struggling to make the sort of headway that will see us to the finish line this side of tomorrow.

As the darkness deepens towards night, one thing brightens ahead of us, the red lights of Netheravon air field, shining like a guiding star to the south. Netheravon airfield is a military base and the oldest continually operated airfield in the world having been established in 1913 by the Royal Flying Corps, the predecessor of the RAF. Its black and white buildings and grass strip lie just above the Avon on the river’s east terrace and now play host to the army parachute association and several parachute display teams. Its red lights will be our beacon for some time now.

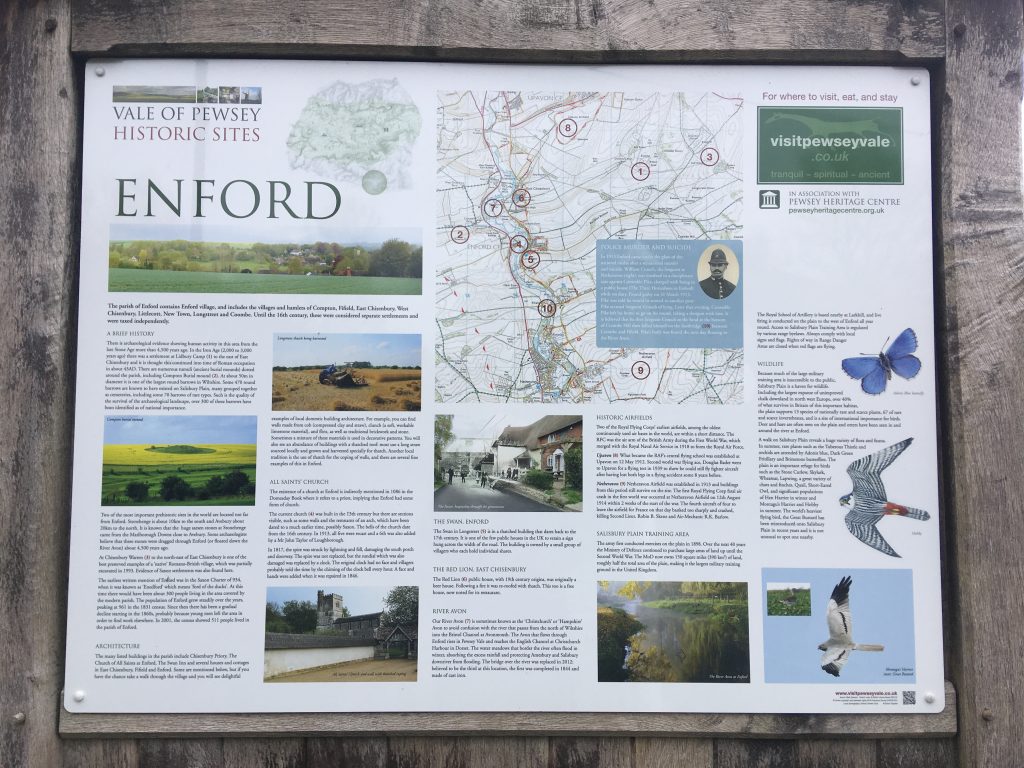

I wait for Clive before we cross a field in darkness heading slightly down hill before locating an uneven staircase of rough timber steps. These take us steeply down through a small wood to the road below, our torches required for the first time along with cautious feet. We cross the road to the village of Enford and feel reassured to be on firm footings, no more climbs ahead. It is nearly the shortest day of the year and the night is upon us but, fortunately, our way ahead now follows the river valley floor spending a significant amount of time on metalled roads.

Villages with lit pavements are spaced regularly along the upper Avon valley, never separated by more than a mile of the otherwise dark winding lanes and footpaths. Their names, Enford, Coombe, Fifield, Fittleton, Haxton, Netheravon. Figheldean, and Ablington often reveal either their river position or who founded the settlements in Saxon times – Fitela’s tun (settlement), Fygela’s denu (large valley) and Ablington, the settlement of Ealdbeald.

Despite the relatively easy going the next mile and a half proves torturous for Clive. He desperately wants to finish the walk but it is now that I realise he really isn’t going to. Knowing that he needs to reach that decision himself, and because I need to keep some rhythm going myself, I stride ahead into Enford. As I pass the Swan pub, where at one point during the planning I was hoping we might stop for a pint to jolly us along, a stout man in country wax coat and hat, possibly the landlord, comments, ‘it’s a bit late to be out walking’. I look at my watch: it is ten past five! Not sure how to reply to this, I mumble some sort of vague agreement and continue past the shut doors and below the once-welcoming sign of the inn, wondering what words of wisdom he might have for Clive as he painfully brings up the rear, shuffling along in his fluorescent jacket. Keen to keep moving, for now I leave Clive to his fate.

A little further on two cars are blocking the road having come to a halt next to each other. It looks as though there has been an accident, the drivers not giving way to each other perhaps on the narrow lane. Nearing, I can see the occupants have their windows down and are in conversation. Am I going to witness an unpleasant scene, I wonder. As I get closer, however, I realise that the two young lady drivers have just stopped for a gossip as they pass. The road being completely blocked by their vehicles I have to walk in between them potentially interrupting the flow of their chat. Bizarrely I find myself apologising as I do so, even though neither of them seems to notice me squeeze through the gap.

Once I get to the end of the village it feels appropriate to wait for my walking partner and before too long I can see him approaching – I knew that jacket would come in useful. Clive has come to the decision that he can’t go on. It is a real shame because I know he doesn’t want to quit and we have already done the tough bit. But he knows that he has no choice.

He will, however, have to keep going for a little longer. Our sleepy lane closely follows the eastern bank of the river but on the other side is a busier road if we can get across to it. I just need Clive to get himself to Coombe and then over the river to Fifield where I feel sure there will be a bus stop. We walk together along a straight flat bit of road that runs below damp trees before a few houses herald the village. We turn off right just beyond a wall onto a stony path. The path is dark as we cross the swollen river on a low metal footbridge, the fast flowing waters rushing noisily inches below our feet.

The rise up the lane to the main road gives Clive a few problems but my phone has told me that a bus to Durrington is due and that keeps him going. We haven’t been at the bus stop more than 2 minutes when the red double-decker looms into view, its X5 route number shining brightly on its front. An outstretched arm stops its progress, Clive climbs aboard and with a relieved wave is gone.

I have about 5 miles left to go on my own but although my legs are a little tired the thought that Clive will arrive at our destination well before me urges me on. I have made a reservation for 18:30 at the appropriately named Stonehenge Inn to celebrate our arrival in Durrington. The December 2020 national rules state that you can only visit a pub with someone not in your household if you book a table outside and order a meal to go with your drink. No doubt Clive will head straight there to secure our table.

I had come off the route to get to the main road and it takes me a little while in the dark to find the footpath that runs off across a field but soon enough I am back on track. I have done a lot of walking on my own, especially during the lock-down year of 2020, but walking alone along a path I don’t know in the dark and near a flooding river does make me slightly nervous. I cross several flat fields, the faint path running fortunately straight from gate to gate. Black woods hide the river to my left, the main road buzzing with traffic high up on the bank to my right.

My map tells of man-made fishing lakes dug nearby to my left as my route ahead narrows to a more defined path. I’m now next to the river again on a muddy track my torch light reflecting off its swirling surface, tall trees close on my right overhang my way and high to the left the red beacon of the airfield glows. I emerge from the dark to reach a road and continue in the same direction towards the sound of a rushing weir. Within a few yards I am passing an old red brick mill filling the gap between road and river that gives me an extra bounce to my step: as I walk by I see the building is now the home of Stonehenge Ales. The idea of not-too-distant refreshment gives me overwhelming encouragement and I quicken my step towards the village of Netheravon.

After the few settlements we have passed through today, Netheravon feels more like a small town. I pass the working men’s club and follow its main road, the way lined by houses. A Victorian terrace on the left faces detached houses with sloping driveways, and shortly I see my first shop of the day, a grocer’s busily open. A huge conifer marks a fork in the road where I head away from the village, its impressive Norman church across the water meadows to my right. Shortly I cross the river by way of a long, very narrow, stone road bridge. The lack of a pavement hastens my way across in the dark, despite a lone cyclist being the only other user. Once over the racing waters, it isn’t long before I turn off the road again into more familiar dark fields, tall trees just showing against the sky in the distance.

After crossing several field boundaries and a silently working sewage works I arrive at a gate that leads back onto the lane that I had last been on with Clive. Looking at the map I see that I am standing below ‘Gallows Barrow’, presumably named after its secondary purpose as a site for a gibbet in the past. As we saw on Morgan’s Hill this morning gallows were often sited on crossroads to give ‘encouragement’ to the maximum number of passers by. This would have been a lonely, eerie place once upon a time on a dark winter’s night; I turn right towards Figheldean (pronounced locally as File-dean).

My first map issue of the night means that I miss an instruction to head into the woods and instead follow the road down to the village, the river now far below me on the right. As I pass church and graveyard I decide my misread was a good thing: now I am walking on pavements through the well-lit village as opposed to dark paths behind houses where the gallows’ ghosts might yet roam! Christmas lights sparkle here on house fronts and, in many of the windows, trees stand merrily adorned – I feel a warmth of happiness. I like Figheldean with its mix of houses, old thatched cottages rubbing shoulders with modern housing and the odd bungalow. At the end of the village the road turns east past a former school to run uphill into the conjoined village of Ablington..

I look for a sign off to the right and am soon back on a footpath that briefly hugs a rendered wall before leading me into the darkness of fields once more. Over a stile I cross a farm lane onto a track which passes widely between tall trees. The Great Stones Way guidebook describes this track as ‘muddy’. Considering the book doesn’t know when its reader is walking this must be an all year, all weather characteristic. I can certainly guarantee that in December after heavy rain ‘muddy’ is an understatement. My over-ankle walking boots are threatened with being swamped if I make a wrong choice of step, and more than once I do, cold liquid oozing over the tops. The mud continues for some time along this deeply dark woodland track but soon enough the worst is past as the way runs gently uphill, my spirits in any case not dampened even if my socks are.

Over a private drive and onto a narrow footpath, pleasantly hard under foot, I start to feel like I am closing in on my destination, Durrington being the next major settlement marked on the map. A sudden worry causes me to call Clive to make sure he has arrived and that our table is still secured at the pub despite us being already quite late. I half expect him to be enjoying at least his second pint by now but he explains that he hasn’t long arrived. In a panic, which is not too strong a word, I call the pub to get reassurance which, after a slightly agonising wait, is duly delivered. Now, all being well, I can enjoy the final approach.

Leaving the woods I come onto a common, the path showing, in my torchlight, to head straight towards some houses a few hundred yards in front of me. As I cross a concrete tank track (confirming this is still army territory) and a grassy ditch I can hear voices full of Christmas cheer coming from the gardens ahead. The path takes me between houses and I can see the merry-makers inside laughing and finger-snacking, drinks being topped up as upbeat music escapes the windows left open for the unseasonably warm winter air. Not far now!

By the side of a wood the path leads me, then across an open hillside field. A kissing gate gives on to a road where I eagerly turn right, past a couple of redbrick thatched cottages, and a short distance down to the river again, 25 feet wide now and fast flowing. I cross via a metal footbridge, the water swirling inkly below me, and bear right along the river bank and onto a lane that urges me on between hedges. The buildings of Avon College loom large in the darkness on my left like moored ships in a midnight harbour.

The lane soon meets a road which I join to head straight on towards All Saints Church, my pace quickening if anything. Now properly within Durrington I turn left past the church at a triangular junction in the middle of which stands a war memorial in the form of a cross. The cross stands on top of a rugged plinth which must have belonged to a medieval pilgrim’s or market cross. A little further on, at a local shop still open and busy with young shoppers, I turn right onto Stonehenge Road, yes, Stonehenge Road.

This last straight climb feels interminable until my destination at last shows itself lit on the hill top, not Stonehenge itself of course, but the Stonehenge Inn. I wonder if this is what the travellers felt when they arrived at the village at Durrington Walls four and a half thousand years ago: relief at having completed the journey, eager expectation of food and drink and excitement at the prospect of the ceremonies at Stonehenge the next day. At the moment it feels like I have walked twenty six miles just for a pint of real ale, my phone advertising that I have taken over 62,000 steps to get here. It is 19.55.

Clive is patiently waiting. We parked vehicles here yesterday on the back road outside the pub; this will form our campsite for the night. He hasn’t been here that long, the bus journey having take him on an unexpected sight-seeing route of the region, so it’s good to see he is still in good humour. He has already changed out of his walking clothes and I now peel off my muddy outside layer and don clean trousers and shoes. A clean shirt, jumper and down jacket and I am also ready for the pub.

In 2019 an artist called Rhys Bliszko was commissioned by the pub landlord, Daniel King, to build a mini concrete replica of Stonehenge outside his pub and we admire this now, briefly, on our way past. After an initial worrying confusion, we are taken to a table in the temporary marquee erected outside the main building. Within a few minutes the first part of my order arrives: a pint of IPA from the Stonehenge Ales brewery I passed an hour or so ago. Everything is coming together very nicely: Stonehenge Ale in the Stonehenge Inn next to a model Stonehenge. The real thing, however, must wait till dawn tomorrow. Read Part III to discover how we get on.